Crafting a Better Way

Darcy SmithShare

Print

Print

In a 1906 article in The Craftsman, you’ll find as good a summary of the Arts and Crafts philosophy as there is, written by Gustav Stickley himself: “…not the mere idea of doing things by hand, but the putting of thought, care, and individuality into the task of making honestly and well something that satisfies a real need.” He goes on to put the artisan squarely at the center of the picture, yet at the same time rejects the notion that modern machinery is a betrayal of craftsmanship.

…given the real need for production and the fundamental desire for honest self-expression, the machine can be put to all its legitimate uses as an aid to, and preparation for, the work of the hand, and the result be quite as vital and satisfying as the best work of the hand alone.

– G. Stickley, "The Use and Abuse of Machinery, and its Relation to the Arts and Crafts"

From its earliest days, Stickley furniture had craftsmanship at its core, and embraced all methods—from old-world joinery to new technology—that made it easier and better. While establishing Arts and Crafts as a significant design movement, both Gustav and Leopold Stickley relied on a combination of traditional and new materials and techniques. Most important was the use of oak, a dependable American hardwood which when quartersawn revealed a unique “ray flake” grain pattern. Showcasing the ray flake was so important to Gus that he applied veneers to surfaces where it otherwise wouldn’t appear, such as two sides of a square post. Years later, Leopold improved on this by developing the “quadralinear” post; in this technique, quartersawn boards are mitered around a center core, a stronger and more lasting solution to creating four sides of visible grain.

Components of a quadralinear post

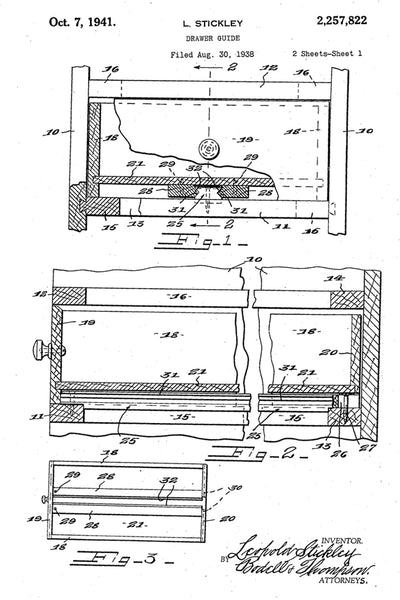

The brothers also relied heavily on traditional forms of joinery, such as mortise-and-tenon and dovetail joints. The mortise and tenon in particular had the advantage not just of strength and reliability—in its exposed forms, it contributed to the beauty and character of Arts and Crafts furniture. With a glance, you could see the craftsman at work. Attention was also paid to the parts of a cabinet that weren’t seen. Leopold Stickley worked hard to solve the problem of constant friction from drawer bottoms causing deterioration in the cross rail. His side-hung, center-guided drawer, one of many designs he patented over his long career, ensured smooth movement without friction and created unmatched strength in the case. This was a key feature that we chose to include in the 1989 reissue of the Mission Collection. width="267"]

It’s a point of pride at today’s L. & J.G. Stickley that we’ve never abandoned the time-honored techniques that worked so well for Gus and Leopold. And those techniques are not confined to Mission styles! On a visit to our Manlius, New York, factory in 2021, you’ll see craftsmen and craftswomen building furniture with pinned or keyed mortise-and-tenon joinery, through-tenons, and other exposed and non-exposed forms (even when the joinery is invisible, you enjoy its benefits).

Drawers are still assembled with precise dovetailing, and they’re hand-fitted, side-hung, and center-guided in true Leopold fashion. Quadralinear posts remain an iconic feature of classic Stickley designs.

Side-hung, center-guided drawers

We also take the time and effort to create book-matched panels: splitting boards into thinner pieces in order to replicate and align the grain to a beautiful effect.

In a case of honoring the original while reimagining it, we’ve developed new techniques for recreating Harvey Ellis inlay designs that draw on our expertise with wood, using a palette of raw and dyed woods in place of metals. And talented artisans still spend painstaking hours hand-carving the exquisite details found on many pieces. Perhaps no piece in our history shows off Stickley’s range of skills better than the Bombé Chest-on-Chest from our former Stickley Williamsburg Reserve Collection. From its meticulously shaped and hand-fitted drawers to its many detailed carvings, it is a masterpiece of craftsmanship.

Crafting the Bombé Chest-on-Chest

Lumber being prepared in our Rough Mill

As Gustav Stickley reminded us in The Craftsman, the demands of production often require the aid of machinery, and we take full advantage of both vintage and modern tools and technology. At the point where raw lumber enters the factory, a Rip First machine uses x-rays and optical scans to detect internal and external defects and trim them away.

An example of our CNC machinery

The flawed scraps are then fed to our boiler to heat the facility, and the best-quality wood moves on. (While in Gus’s day wood waste was as much as 50%, we’re proud to say that nearly 100% of the wood we receive is used in furniture or some other capacity.) Elsewhere in the plant, a planer from the 1950s and two other machines with a combined 60 years of service work alongside a variety of state-of-the-art devices. A double-end tenoner uses lasers to measure and place precise cuts for tenons, so crucial to our joinery. And two types of CNC (“computer numerical control”) routers use a combination of human operators and computer technology to cut notches, drill holes, cut tenons, and more; these remarkable machines can even swap out their own tool bits automatically to complete a series of programmed tasks. There are many more steps en route to a completed piece of Stickley furniture, including machine- and hand-sanding, assembly, finishing, and trim. Along the way, each piece is touched by the hands of many artisans, from master craftsmen in their seventies to young people honing their skills. A key moment in the process is when Fit Operators complete a cabinet or table and permanently stamp their initials on it, certifying that the work meets his or her standard of excellence. While machines are used as “a tool in the hand of a skilled worker”, Stickley craftsmanship is still very much a meaningful human accomplishment.

Applying the finishing touches

Additional sources: Stickley, Gustav. "The Use and Abuse of Machinery, and its Relation to the Arts and Crafts."

The Craftsman 11, No 2, November 1906, pages 202-07.

Edward Audi, President

Amanda Clifford, Director, The Stickley Museum

Thomas Q. Graham, Quality Manager